Confucianism and Its Impact on Chinese Art and Culture

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ec/48/ec4893b8-64b8-4e25-b21d-f5cdf8414cd6/main-collage.jpg)

For the past yearI have been working with Britain'southward BBC television to make a documentary serial on the history of women. In the latest round of filming there was an incident that haunts me. It took place during a segment on the social changes that afflicted Chinese women in the late 13th century.

These changes tin can exist illustrated past the practice of female pes-bounden. Some early bear witness for it comes from the tomb of Lady Huang Sheng, the married woman of an imperial clansman, who died in 1243. Archaeologists discovered tiny, misshapen feet that had been wrapped in gauze and placed inside peculiarly shaped "lotus shoes." For one of my pieces on photographic camera, I balanced a pair of embroidered doll shoes in the palm of my hand, as I talked about Lady Huang and the origins of foot-bounden. When it was over, I turned to the museum curator who had given me the shoes and made some comment about the silliness of using toy shoes. This was when I was informed that I had been belongings the real thing. The miniature "doll" shoes had in fact been worn by a human. The daze of discovery was similar being doused with a bucket of freezing h2o.

Foot-bounden is said to have been inspired by a tenth-century court dancer named Yao Niang who bound her feet into the shape of a new moon. She entranced Emperor Li Yu past dancing on her toes within a six-foot golden lotus festooned with ribbons and precious stones. In addition to altering the shape of the pes, the practice also produced a particular sort of gait that relied on the thigh and buttock muscles for support. From the first, pes-binding was imbued with erotic overtones. Gradually, other court ladies—with money, time and a void to fill—took up foot-binding, making it a status symbol among the aristocracy.

A modest pes in Mainland china, no different from a tiny waist in Victorian England, represented the height of female refinement. For families with marriageable daughters, foot size translated into its own form of currency and a means of achieving upward mobility. The almost desirable bride possessed a 3-inch foot, known as a "golden lotus." It was respectable to take iv-inch feet—a silver lotus—simply feet five inches or longer were dismissed as iron lotuses. The wedlock prospects for such a girl were dim indeed.

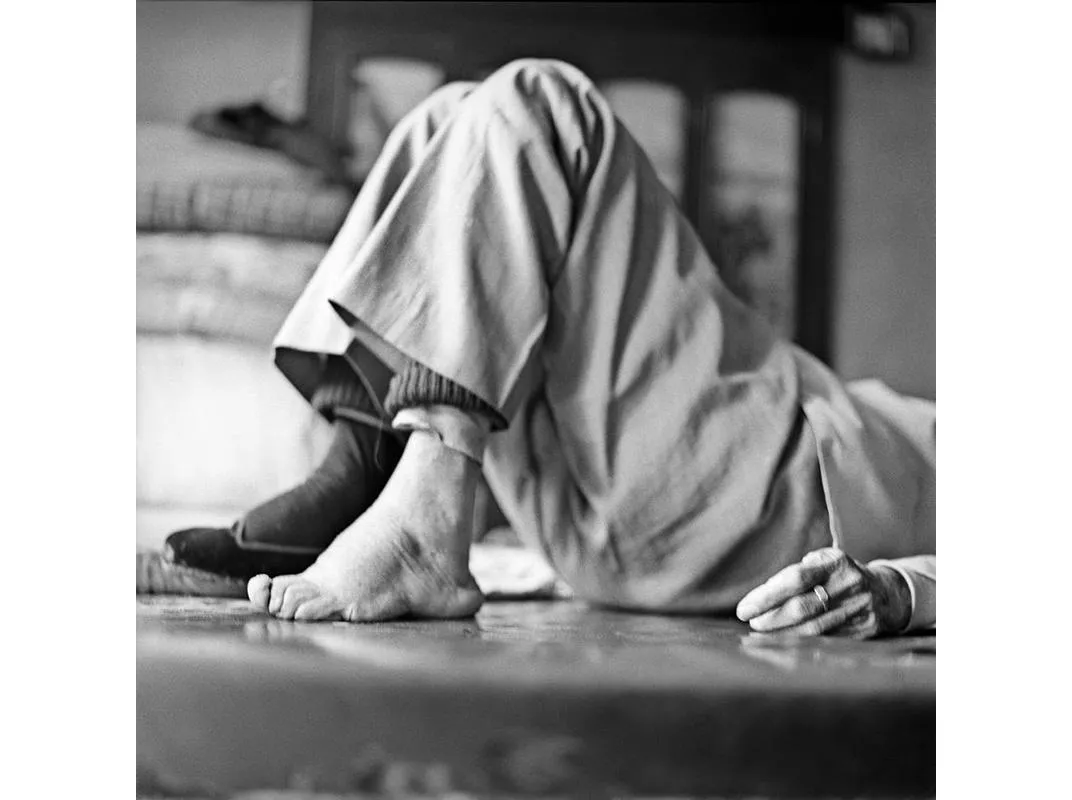

As I held the lotus shoes in my hand, it was horrifying to realize that every attribute of women'southward dazzler was intimately bound up with pain. Placed side by side, the shoes were the length of my iPhone and less than a half-inch wider. My index finger was bigger than the "toe" of the shoe. It was obvious why the process had to begin in childhood when a girl was five or vi.

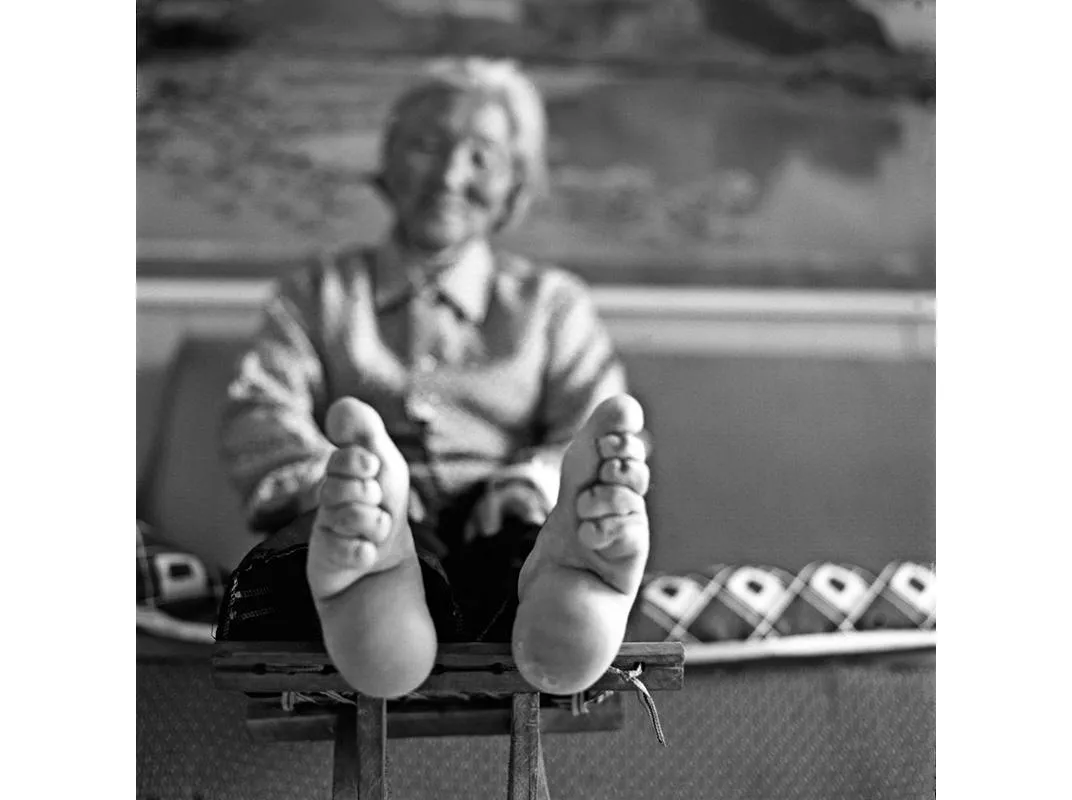

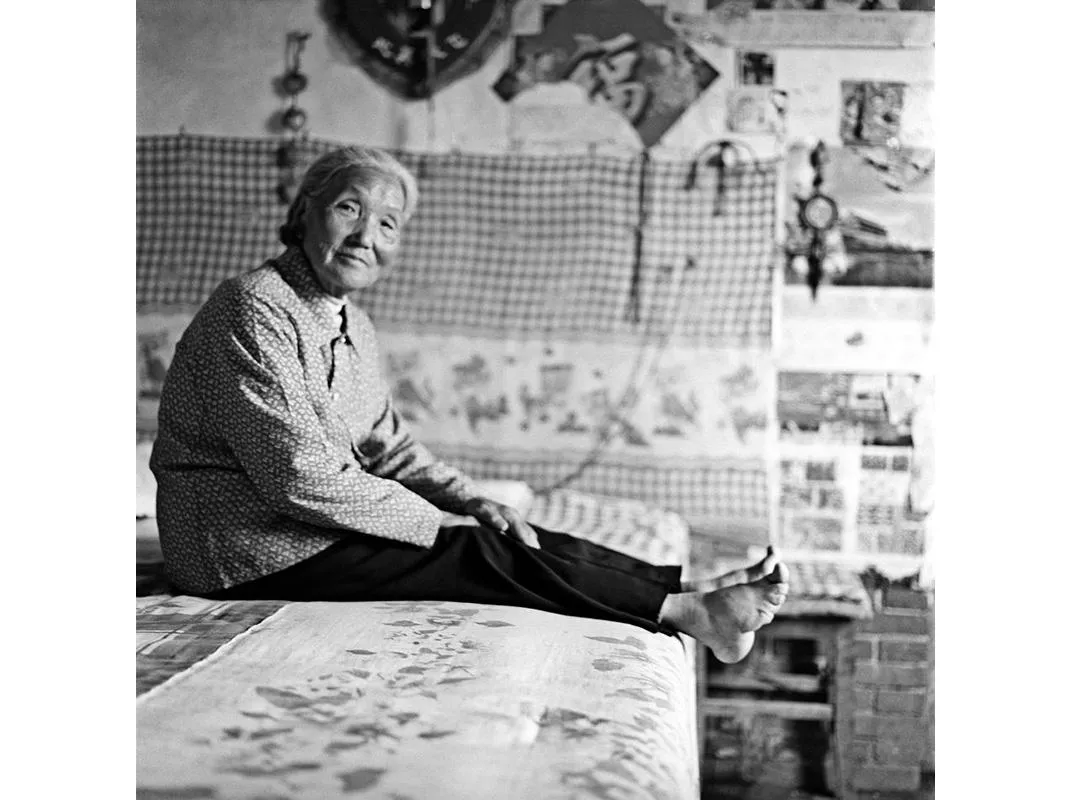

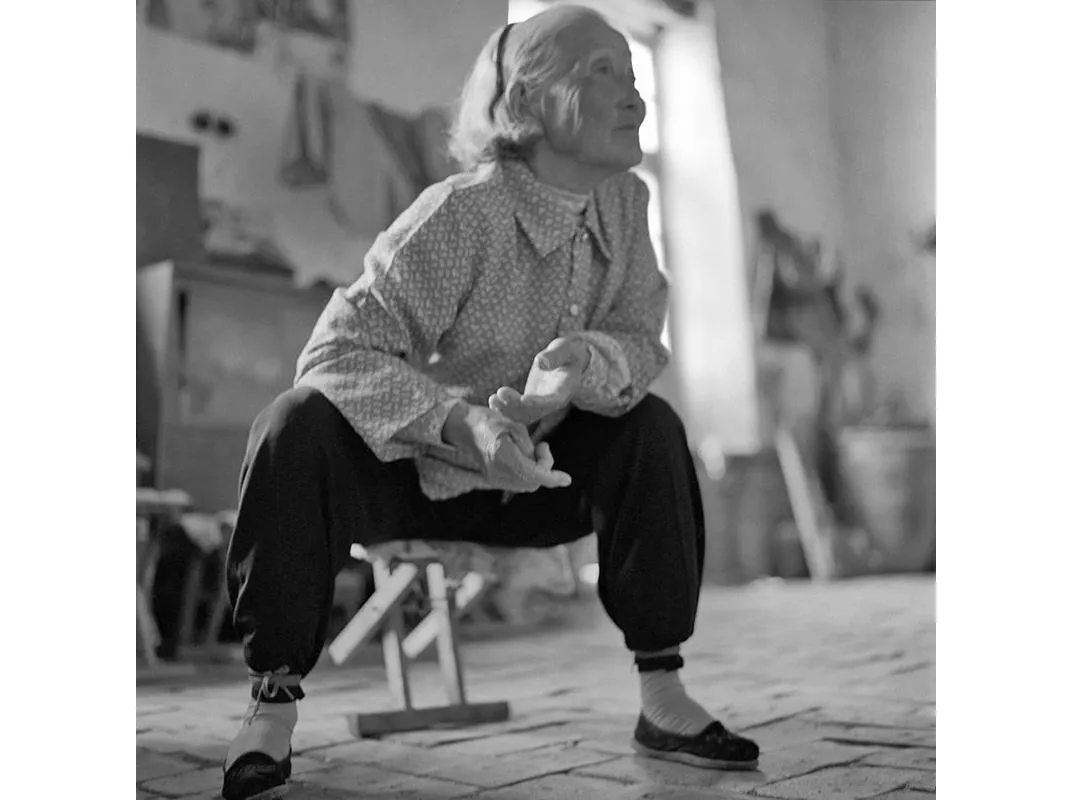

Start, her feet were plunged into hot water and her toenails clipped brusque. Then the anxiety were massaged and oiled before all the toes, except the big toes, were broken and bound apartment against the sole, making a triangle shape. Adjacent, her arch was strained as the foot was aptitude double. Finally, the feet were bound in place using a silk strip measuring x anxiety long and two inches broad. These wrappings were briefly removed every two days to prevent blood and pus from infecting the pes. Sometimes "backlog" flesh was cut away or encouraged to rot. The girls were forced to walk long distances in lodge to hasten the breaking of their arches. Over time the wrappings became tighter and the shoes smaller as the heel and sole were crushed together. After ii years the procedure was complete, creating a deep scissure that could hold a coin in place. Once a pes had been crushed and bound, the shape could not be reversed without a woman undergoing the same pain all over over again.

***

Equally the do of foot-binding makes brutally clear, social forces in China so subjugated women. And the impact can be appreciated past considering 3 of China's greatest female figures: the politician Shangguan Wan'er (664-710), the poet Li Qing-zhao (1084-c.1151) and the warrior Liang Hongyu (c.1100-1135). All three women lived before foot-binding became the norm. They had distinguished themselves in their ain right—not as voices behind the throne, or muses to inspire others, simply equally self-directed agents. Though none is well known in the West, the women are household names in Communist china.

Shangguan began her life under unfortunate circumstances. She was built-in the year that her grandfather, the chancellor to Emperor Gaozong, was implicated in a political conspiracy against the emperor'southward powerful wife, Empress Wu Zetian. Afterward the plot was exposed, the irate empress had the male members of the Shangguan family executed and all the female members enslaved. Nevertheless, after beingness informed of the 14-year-onetime Shangguan Wan'er'south exceptional brilliance equally a poet and scribe, the empress promptly employed the girl as her personal secretary. Thus began an extraordinary 27-year relationship betwixt China'southward only female person emperor and the woman whose family she had destroyed.

Wu eventually promoted Shangguan from cultural minister to master minister, giving her charge of drafting the majestic edicts and decrees. The position was as dangerous as it had been during her grandfather'southward time. On one occasion the empress signed her death warrant only to have the penalty commuted at the last minute to facial disfigurement. Shangguan survived the empress'southward downfall in 705, merely not the political turmoil that followed. She could not assistance becoming embroiled in the surviving progeny's plots and counterplots for the throne. In 710 she was persuaded or forced to typhoon a fake document that acceded power to the Dowager Empress Wei. During the bloody clashes that erupted betwixt the factions, Shangguan was dragged from her business firm and beheaded.

A after emperor had her poetry collected and recorded for posterity. Many of her poems had been written at imperial command to commemorate a detail state occasion. Simply she also contributed to the development of the "manor poem," a grade of poesy that celebrates the courtier who willingly chooses the simple, pastoral life.

Shangguan is considered by some scholars to be one of the forebears of the Loftier Tang, a aureate age in Chinese poetry. Still, her piece of work pales in significance compared with the poems of Li Qingzhao, whose surviving relics are kept in a museum in her hometown of Jinan—the "City of Springs"—in Shandong province.

Li lived during ane of the more chaotic times of the Vocal era, when the state was divided into northern Red china under the Jin dynasty and southern Cathay under the Song. Her husband was a mid-ranking official in the Song regime. They shared an intense passion for art and poesy and were gorging collectors of ancient texts. Li was in her 40s when her hubby died, consigning her to an increasingly fraught and penurious widowhood that lasted for another two decades. At one signal she made a disastrous matrimony to a man whom she divorced after a few months. An exponent of ci poesy—lyric verse written to popular tunes, Li poured out her feelings well-nigh her married man, her widowhood and her subsequent unhappiness. She eventually settled in Lin'an, the capital of the southern Vocal.

Li'southward afterwards poems became increasingly morose and despairing. But her before works are total of joie de vivre and erotic desire. Similar this i attributed to her:

... I finish tuning the pipes

face the floral mirror

thinly dressed

crimson silken shift

translucent

over icelike flesh

lustrous

in snowpale foam

glistening scented oils

and express mirth

to my sweet friend

this night

you are within

my silken curtains

your pillow, your mat

will grow cold.

Literary critics in afterward dynasties struggled to reconcile the woman with the poetry, finding her remarriage and subsequent divorce an affront to Neo-Confucian morals. Ironically, between Li and her near-contemporary Liang Hongyu, the former was regarded every bit the more transgressive. Liang was an ex-courtesan who had followed her soldier-husband from camp to army camp. Already beyond the pale of respectability, she was not subjected to the usual censure reserved for women who stepped beyond the nei —the female sphere of domestic skills and household management—to enter the wei , the and so-called male realm of literary learning and public service.

Liang grew up at a military machine base commanded by her father. Her didactics included military machine drills and learning the martial arts. In 1121, she met her married man, a inferior officer named Han Shizhong. With her assist he rose to become a general, and together they formed a unique military partnership, defending northern and central China against incursions by the Jurchen confederation known as the Jin kingdom.

In 1127, Jin forces captured the Song uppercase at Bianjing, forcing the Chinese to establish a new capital in the southern part of the country. The defeat almost led to a coup d'état, but Liang and her husband were among the military commanders who sided with the beleaguered authorities. She was awarded the championship "Lady Defender" for her bravery. Iii years later, Liang accomplished immortality for her part in a naval engagement on the Yangtze River known equally the Battle of Huangtiandang. Using a combination of drums and flags, she was able to point the position of the Jin fleet to her hubby. The general cornered the fleet and held information technology for 48 days.

Liang and Han lie buried together in a tomb at the foot of Lingyan Mount. Her reputation as a national heroine remained such that her biography was included in the 16th-century Sketch of a Model for Women by Lady Wang, one of the four books that became the standard Confucian classics texts for women's education.

Though it may not seem obvious, the reasons that the Neo-Confucians classed Liang as commendable, but not Shangguan or Li, were office of the same societal impulses that led to the widespread acceptance of foot-binding. Get-go and foremost, Liang's story demonstrated her unshakable devotion to her male parent, and so to her husband, and through him to the Song state. As such, Liang fulfilled her duty of obedience to the proper (male) order of club.

The Song dynasty was a time of tremendous economic growth, but likewise peachy social insecurity. In contrast to medieval Europe, under the Song emperors, form status was no longer something inherited but earned through open up competition. The old Chinese aloof families found themselves displaced by a meritocratic class called the literati. Entrance was gained via a rigorous ready of civil service exams that measured mastery of the Confucian catechism. Not surprisingly, as intellectual prowess came to be valued more highly than animal strength, cultural attitudes regarding masculine and feminine norms shifted toward more than rarefied ideals.

Foot-bounden, which started out equally a stylish impulse, became an expression of Han identity later the Mongols invaded China in 1279. The fact that it was merely performed by Chinese women turned the exercise into a kind of autograph for indigenous pride. Periodic attempts to ban information technology, as the Manchus tried in the 17th century, were never nearly foot-bounden itself just what information technology symbolized. To the Chinese, the practise was daily proof of their cultural superiority to the uncouth barbarians who ruled them. It became, like Confucianism, another point of divergence between the Han and the rest of the world. Ironically, although Confucian scholars had originally condemned pes-binding as frivolous, a woman'south adherence to both became conflated as a single act.

Earlier forms of Confucianism had stressed filial piety, duty and learning. The form that developed during the Song era, Neo-Confucianism, was the closest Cathay had to a country faith. It stressed the indivisibility of social harmony, moral orthodoxy and ritualized beliefs. For women, Neo-Confucianism placed extra emphasis on guiltlessness, obedience and diligence. A good wife should have no desire other than to serve her husband, no ambition other than to produce a son, and no interest beyond subjugating herself to her married man's family—meaning, among other things, she must never remarry if widowed. Every Confucian primer on moral female beliefs included examples of women who were prepared to dice or suffer mutilation to testify their delivery to the "Manner of the Sages." The deed of foot-bounden—the pain involved and the physical limitations it created—became a woman's daily demonstration of her own commitment to Confucian values.

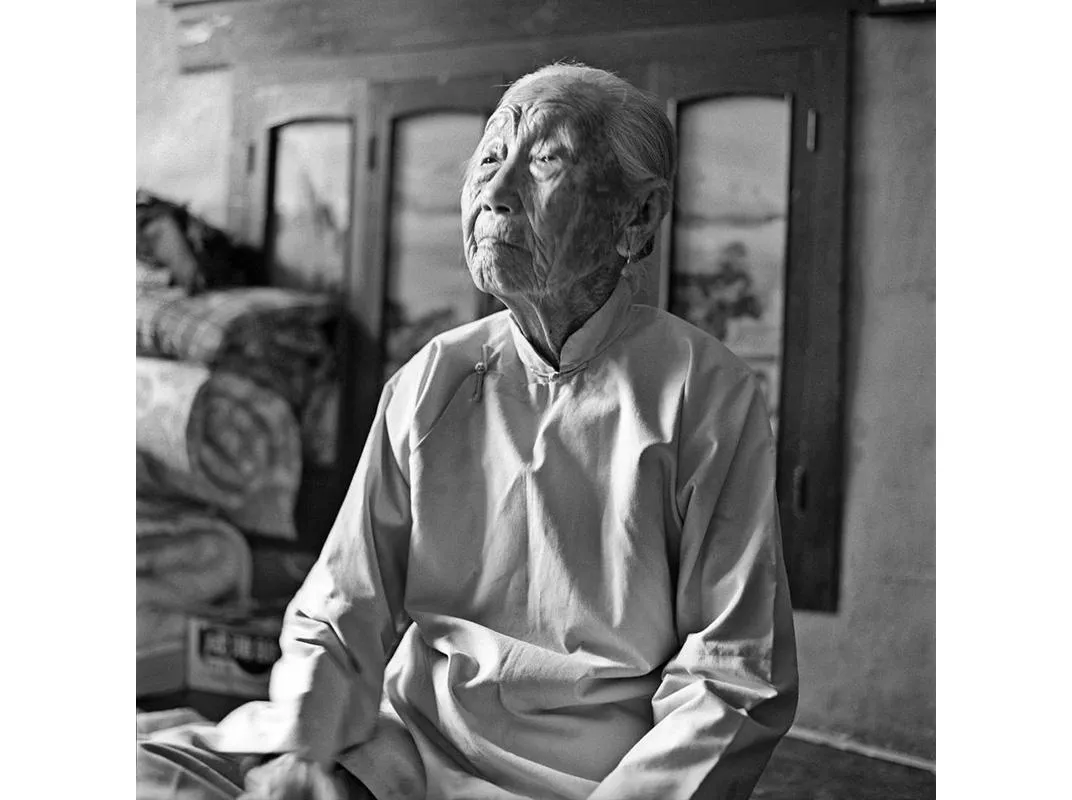

The truth, no matter how unpalatable, is that pes-binding was experienced, perpetuated and administered by women. Though utterly rejected in Communist china now—the last shoe factory making lotus shoes closed in 1999—it survived for a thousand years in function because of women'southward emotional investment in the practice. The lotus shoe is a reminder that the history of women did not follow a straight line from misery to progress, nor is information technology merely a curlicue of patriarchy writ large. Shangguan, Li and Liang had few peers in Europe in their own time. But with the advent of foot-binding, their spiritual descendants were in the West. Meanwhile, for the adjacent 1,000 years, Chinese women directed their energies and talents toward achieving a 3-inch version of concrete perfection.

Every Step a Lotus: Shoes for Bound Feet

Cinderella'due south Sisters: A Revisionist History of Footbinding

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/why-footbinding-persisted-china-millennium-180953971/

0 Response to "Confucianism and Its Impact on Chinese Art and Culture"

Post a Comment